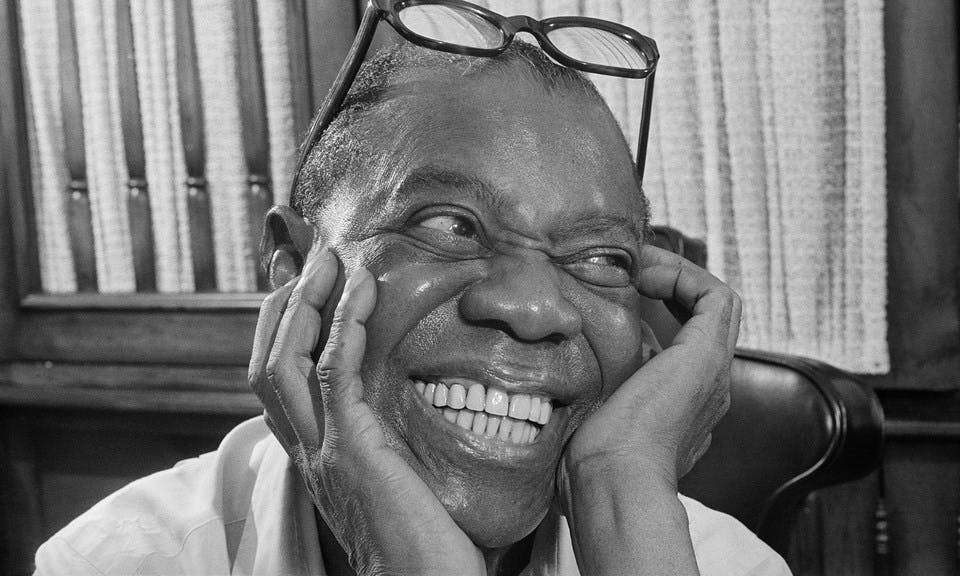

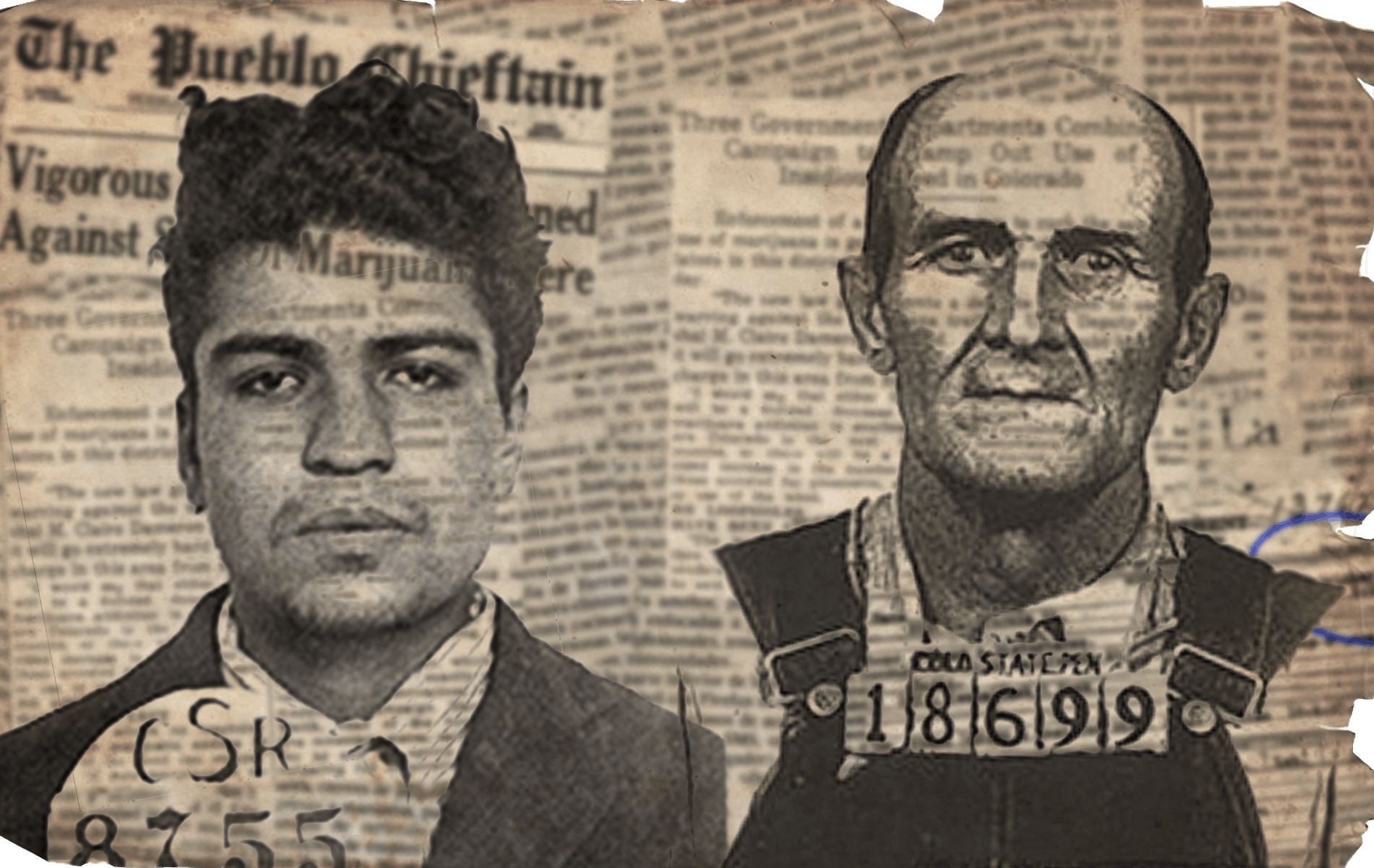

Harry J. Anslinger retired from the now-defunct Federal Bureau of Narcotics 60 years ago, but he remains the ultimate boogey man of every pot smoker in the world—a kind of atavistic “human paraquat” whose overt racism and institutional cruelty remains at the heart of the ongoing global War on Drugs.

Anslinger returned to public consciousness last week with the release (on Hulu) of The United States vs. Billie Holiday, a new film from Lee Daniels (Push, Empire) telling the true story of how America’s first “drug czar” used the full power of federal law enforcement to target the legendary jazz singer for multiple arrests, ultimately hounding her into an early grave.

Fed narcotics agency built racism into its work

Anchored by a brilliant Golden-Globe-winning performance from Andra Day in the title role, the story—based in part on Johann Hari’s insightful book Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs—rightly casts Anslinger as the villain. But with the narrative focused on Holiday herself, and a real-life undercover FBN agent tasked with taking her down, the head of the FBN doesn’t get a lot of screen time.

That means viewers outraged by the events depicted will likely be left with a lot of questions about the man behind this modern-day inquisition.

Harry Anslinger’s role

Speaking as someone who once took a road trip to visit Harry Anslinger’s grave in rural Pennsylvania, smoke a joint, plant a seed, and “water it in”—see a very special episode of my podcast Great Moments in Weed History—this is a piece of history that must be understood, lest we continue to repeat it endlessly.

For example, Anslinger’s start in law enforcement came as a leading proponent of alcohol prohibition, a position he steadfastly supported despite its failure by every possible metric.

Moving from booze the drugs

By the time the War on Booze ended in 1933, Anslinger had already moved on to enforcing existing prohibitions against opioids and other narcotics, including by spearheading a campaign to target physicians providing maintenance doses to those struggling with addiction. More than 20,000 doctors would be arrested on Anslinger’s orders, effectively ending the practice, while pushing users (including Billie Holiday) to find drugs on the street and creating an incredibly lucrative new revenue stream for organized crime just as the end of the bootlegging era threatened to leave those gangsters high and dry.

Anslinger would eventually come to accept that alcohol prohibition was a terrible failure. But instead of throwing open the taverns, he wanted to double down.

In 1928, he wrote a position paper calling for an extension of the Volstead Act (alcohol prohibition) to target not just those who manufacture, distribute, and sell alcoholic beverages, but also those who buy and consume the drug.

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries nearSix months in prison for buying a bottle

According to Harry’s plan, a first offense for illegal purchase of alcohol would mean a mandatory minimum of six months in prison.

But then two years later—sensing a shift in the prevailing political winds—he abruptly declared Prohibition to be a lost cause.

Though famously, this wasn’t his last attempt at banning something.

On January 14, 1937, Anslinger headed a marijuana conference in Washington, DC, attended by government authorities and academics.

At one point the Treasury Department’s leading chemist asked what effect banning hemp seeds might have on the birdseed industry. Anslinger replied, in all seriousness, that it could make caged birds stop singing.

Not that such a possibility changed the prohibitionists’ minds any.

The only doctor who spoke, opposed prohibition

The men who banned marijuana were similarly unfazed by the testimony of Dr. William C. Woodward of the American Medical Association, the only speaker to present himself as a hostile witness. Both a physician and an attorney, Dr. Woodward basically called bullshit on the entire proceedings:

We are referred to newspaper publications concerning the prevalence of marihuana addiction. We are told that the use of marihuana causes crime.But no evidence has been produced from the Bureau of Prisons to show the number of prisoners who have been found addicted to the marihuana habit.

We have been told that school children are great users of marihuana cigarettes. But no one has been summoned from the Children’s Bureau to show the extent of the habit among children. Inquiry of the Children’s Bureau indicates that they have had no occasion to investigate and know nothing of it….

1937 Act gave Anslinger power to harass jazz artists

With the subsequent passage of the 1937 Marijuana Tax Act, federal cannabis prohibition became the law of the land. Anslinger immediately used his new power to target two groups in particular—Mexican-American immigrants (including many who recently arrived as war refugees) and African-American jazz musicians.

Prior to and even after federal prohibition, a wide range of jazz greats recorded weedy torch songs like Reefer Man (Cab Calloway), If You’re a Viper (Fats Waller), Texas Tea Party (Benny Goodman), Muggles (Louis Armstrong), Gimme a Reefer (Bessie Smith), When I Get Low, I Get High (Ella Fitzgerald), and I’m Feeling High and Happy (Gene Krupa).

A plan to bring down the entire genre of music

In a memo to his FBN field agents, Anslinger detailed a plan to retaliate by taking down the entire jazz scene at once, writing: Please prepare all cases in your jurisdiction involving musicians in violation of the marijuana laws. We will have a great national round-up arrest of all such persons on a single day.

But those plans fizzled, as detailed in Chasing the Scream:

The jazz world had one weapon that saved them: absolute solidarity. Anslinger’s men could find almost no one willing to snitch, and whenever one of them was busted, they all chipped in to bail him out. In the end, the Treasury Department told Anslinger he was wasting his time taking on a community that couldn’t be fractured, so he scaled down his focus until it settled like a laser on a single target—perhaps the greatest female jazz vocalist there ever was.

He wanted to bring the full thump of the federal government down upon that scourge of modern society, his Public Enemy #1: Billie Holiday.

A childhood marked by trauma

After enduring a childhood marked by extreme trauma, abuse and heartbreak, Billie Holiday had developed a substance abuse problem and was widely known to be a user of heroin and other drugs. But that’s not what put a target on her back.

Harry Anslinger’s obsession with Billie Holiday began on the night in 1939 when she sang Strange Fruit in public for the first time. A searing indictment of the lynching of Black people as a means of enforcing white supremacy, the song touched a nerve with audiences, particularly when sung with Holiday’s signature mix of pathos and defiance.

FBI: Stop singing ‘Strange Fruit,’ or else

Almost immediately, the FBN warned her to stop singing Strange Fruit or to face the consequences. She would continue to perform it until her death.

Anslinger sent a Black undercover agent to surveil Billie Holiday. The first time he busted her by pretending to deliver a telegram. After that, he just kept following her.

“I had so many close conversations with her, about so many things,” this narc later reported. “She was the type who would make anyone sympathetic because she was the loving type.”

Set up by her own man

Meanwhile, Billy Holiday made moves to rid herself of another abusive man, her husband and manager Louis McKay, who physically assaulted her to the point she sometimes needed to tape up her ribcage just to sing. When McKay, enraged by Holliday leaving him, learned that Anslinger was on her tail, he traveled to Washington, DC and met with the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

Together they plotted to set Holiday up for another bust.

According to Chasing the Scream:

Billie Holiday was sentenced to a year in a West Virginia prison, where she was forced to go cold turkey and work during the days in a pigsty. In all her time behind bars, she did not sing a note. Upon release, she was stripped of her cabaret performer’s license, on the grounds that listening to her might harm the morals of the public. This meant she wasn’t allowed to sing anywhere that alcohol was served—which included all the jazz clubs in the United States.

Sadistic harassment even in the hospital

When she got out, Anslinger re-assigned the high-profile case to his favorite agent, Colonel George White, who was known as a true sadist. White set Holiday up for her final bust by planting drugs on her while she was in the hospital.

She was then held as a virtual prisoner, denied proper healthcare, any visitors, or even books to read. On the street outside the hospital, protesters held up signs reading “Let Lady Live,” but she would die right there in the hospital, surrounded by cops.

All through the 1950’s, as cannabis continued to spread via the underground, Anslinger would successfully push for increasingly draconian penalties, including for simple possession, by directly linking cannabis and Communism during the height of the red scare. Never mind the complete lack of any credible evidence to back up his claims of a vast plot out of Moscow to enslave America to marijuana addiction.

And so, from its onset, the War on Drugs worked to enforce both white supremacy and the crushing of political dissent—a one-two punch that continues today.