The first Thursday in June marks the opening of a new exhibition at Amsterdam’s Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum: “We Are Mary Jane. Women of Cannabis.” Both timely and engagingly time-tripping, this temporary show sets out to illuminate various roles women have played in a traditionally male-led industry.

At the time of writing this article, plans for the exhibition were still in the works, though Leafly was privy to a verbal preview courtesy of museum curator Gerbrand Korevaar. Subjects range from the 17th-century wheel-bound women, who spun hemp fibers and supplied the Dutch shipping empire with ropes, rigs, and sails, to the hard laborers in Italian and Romanian hemp fields during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

(Courtesy of Karina Hof)

The exhibition even reaches current trends, ranging from topicals by Whoopi & Maya to reproductions of Amy Merrick’s ikebana arrangements (featured in the woman-led weed glossy, Broccoli). Also included is Amsterdam-based photographer Maria Cavali, who contributes images of women “for whom cannabis is an aspect of their daily routine,” says Korevaar.

Within this particular exhibition, as with most that take center stage at the museum, cannabis coverage spans hundreds of years. It dives into cultivators, crafters, and purveyors, but also consumers and proponents of cannabis. What’s more, “We Are Mary Jane” signals that both exhibitors and audiences have moved beyond cannabis itself as the matter for observation as deeper discussions and social issues continue to surge.

Maintaining a Robust and Growing Collection

(Courtesy of Karina Hof)

Once upon a time—founding year 1985, to be precise—the museum’s De Wallen location seemed obvious. A colloquial name for Amsterdam’s once wall-demarcated medieval middle, De Wallen is home to the Red Light District, sex shows and shops, snack and dive bars, plus an array of star-studded coffeeshops. So where better to host a hub of cannabis relics and memorabilia than in the cradle of practices deemed illegal and/or illicit in most other places?

Yet in 2018, the museum’s notorious postal code almost belies its message: though the road to decriminalization and legalization is long and circuitous, cannabis is consumed by all types of good people for all types of good reasons.

In fact, back when Ben Dronkers, founder of giant Dutch seed bank Sensi Seeds, and grow guru Ed Rosenthal opened the institution’s doors, it was called the Hash Info Museum. The two were friends, and “collecting remnants of cannabis culture,” as Korevaar puts it, was something they had in common. “On his travels, Ben landed upon examples of hemp culture worldwide—you know, textiles, spinning materials, pipes, all kinds of things relating to the plant,” explains the curator. Dronkers then realized that he had “a special collection and a passion for this plant,” and in Korevaar’s paraphrasing of his boss: “‘This needs to be shared. Cannabis is all about sharing.’”

“Visitors are usually familiar with coffeeshops but walk out knowing much more about the other uses of this plant.”

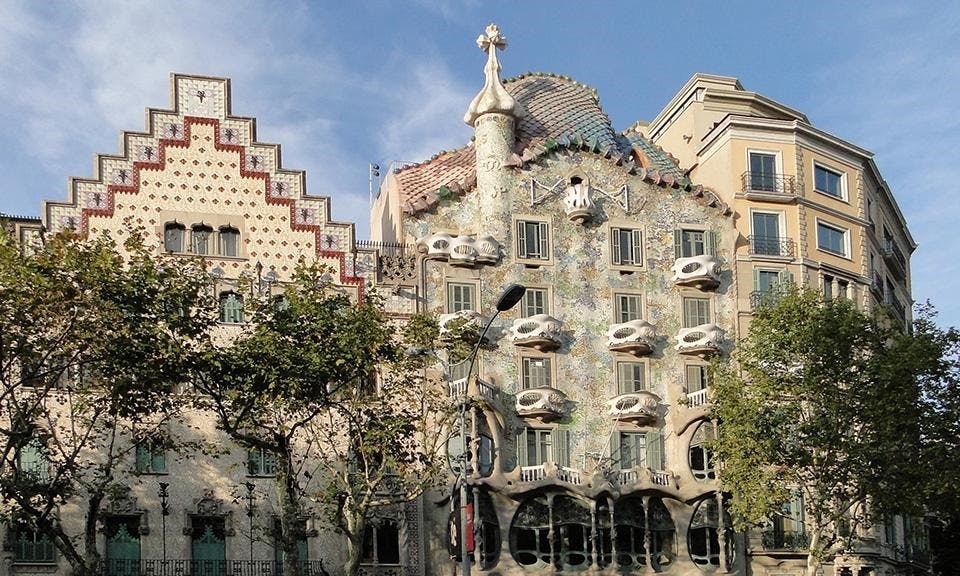

The museum has two branches: the flagship in Amsterdam, which expanded to occupy a second building in 2009; and the Barcelona branch, established in 2012, in a meticulously renovated Modernist palace. The Amsterdam property reportedly receives 100,000 visitors each year, and 70% of those guests also patronize Amsterdam coffeeshops—according to museum studies.

“Visitors are usually familiar with coffeeshops but walk out knowing much more about the other uses of this plant,” says Korevaar. The museum, he emphasizes, is “about spiritual, medicinal, and recreational use. It’s about cultural use, and it’s about industrial use. We try to cover all these things.”

Shop highly rated dispensaries near you

Showing you dispensaries nearHidden Treasures and Legal Troubles

(Courtesy of Karina Hof)

Entering the main house, guests are first greeted by a sculptural rendition of a spread from the Vienna Dioscorides. From Constantinople, circa 512, the illuminated manuscript records hundreds of flora and their medicinal derivations. The word “cannabis” is transliterated into eight ancient scripts—none of which correspond to the eight languages in which the museum’s enjoyable podcatcher tour is available, though all of which attest to cannabis’ pre-Big Pharma polylingual appeal.

Several steps and centuries forward comes the section cataloged as “Coffeeshops of the Golden Age.” Red ochre walls set the atmosphere to Old World, with paintings depicting pipe-touting men in rookhuizen—literally “smoke houses”—essentially proto-coffeeshops. Artists in this genre include Adriaen Brouwer, Hendrick Sorgh, David Teniers the Younger, and Adriaen van Ostade, who, like Dutch contemporaries Rembrandt and Vermeer, captured scenes of everyday 17th-century life. The works are all originals except for Brouwer’s The Smokers, which is a representation of the oil on wood that hangs in New Amsterdam, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“He considered this display to be about smuggling propaganda for illegal activities relating to cannabis. But the museum was sharing information,” Korevaar says, referring to former minister Korthals Altes.

In a lawsuit that ensued, Dronkers triumphed.

“In the end, it was actually good publicity,” laughs Korevaar.

One shelf is still devoted to Mr. Nice, officially Howard Marks, the late Welsh drug smuggler who did seven years in one of the US’s most notorious penitentiaries. His autobiography is propped up alongside an inmate card.

Tracing Cannabis Through the Ages

(Courtesy of Karina Hof)

The museum’s expansive collection includes law enforcement uniform patches, which, decontextualized from their wearers, seem semiotically confused; their vibrantly embroidered sativa and indica leaves communicate a message that reads “pro-pot” far more than “drug bust.” Decades worth of posters and pamphlets document the tediousness of the war on drugs and counter-movements by pro-legalization groups, such as NORML. The labels of 19th-century medicine bottles and boxes advertise salves for many ailments, from head (a “sedative,” sugar-coated and pink) to toe (“a sure corn cure”).

The next room gives some guests their first, if not only, occasion to get close to real, live cannabis. After having plowed through all the texts and images thus far, four plants in a small glassed-in grow room—kitted with lamps and fans, and periodically checked by staff green thumbs—provide a tender sight for the eyes. They invite a momentary contemplation of nature, indoors.

A few steps northward on the same canal-side block is what the museum calls the “Hemp Gallery.” Influenced early on by his friend Jack Herer and his seminal book The Emperor Wears No Clothes, Dronkers has amassed plenty of hemp curiosa as well as merchandise from its industrial application (which he has become well familiar with through the business of HempFlax, another one of his companies).

Hemp was not only processed for constructing the softer parts of a boat, but also for oil to fuel the lamps by which sailors read the Bible, which was printed on hemp pages.

The gallery’s permanent collection showcases hemp-made items associated with subculture, such as Adidas sneakers, a skateboard, a surfboard, a guitar, and a Be.e electric scooter. Additionally, hemp wares emerge from more mainstream industries, including Mercedes-Benz car doors; oil for quadrupeds, offering a “protective, disinfectant and nourishing effect on hooves and horns”; a Dutch lawyer’s black court robe; Louis Vuitton high-heel sandals; and its ostensibly infinite functions in all dimensions of colonial maritime life. Hemp was not only processed for constructing the softer parts of a boat, but also for fishing nets, sailors’ uniforms, shipping logs, and oil to fuel the lamps by which sailors read the Bible, which was printed on hemp pages.

(Courtesy of Karina Hof)

It is in this building, too, that “We Are Mary Jane” is scheduled to run until September 23, 2018. The exhibition fills space prior occupied by “Cannabis Cuisine,” an exhibition that ran until April, surveying the plant’s presence in food and drink, something that has just now gotten on the radar of popular culture in the Netherlands.

A plum piece in the permanent collection is a watercolor painting by Mondriaan, circa 1900, before the Dutch artist fully committed to quadrilaterals (and dropped the second “a” from his surname). Entitled “Farmer’s Wife Spinning,” the portrait profiles a seated spinner alone at work, her hands negotiating a tuft of fibers, her black clog cast aside. It fits right in with the exhibition’s other cases of female labor, often done behind the scenes in physical and/or psychological solitude. Although the Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum is shining a brighter light on this farmer’s wife—among other similarly toiling women who have come before and after her—it will be up to the cannabis community worldwide to keep it lit.

As said by Dronkers, “to inform the uninformed and make our visitors aware of the enormous potential of the plant” remains a priority of the museum.